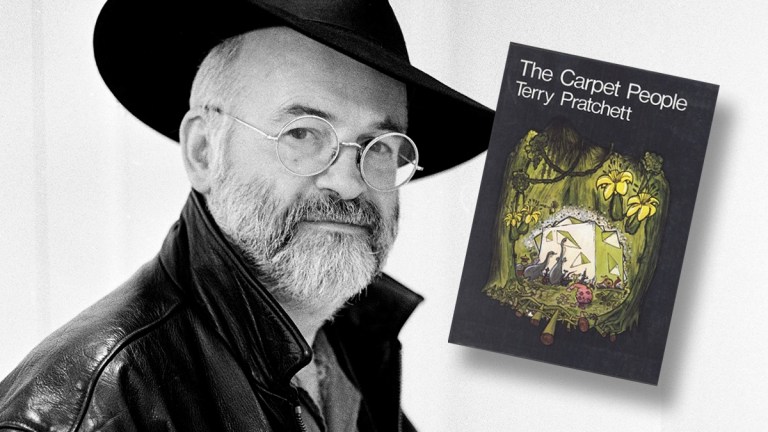

How Terry Pratchett’s First Novel Went From Tolkien Homage To Parody

As Sir Pterry's Discworld celebrates its 40th anniversary, here's how he established his comedic voice through multiple rewrites of his very first novel - The Carpet People.

You can’t buy Terry Pratchett’s first novel – or rather, you can, but it will cost you. A first edition of the original 1971 version of The Carpet People will set you back somewhere between £400 and £1000; Forum Auctions have one on sale with a guide price of £400 – £600. You can, of course, buy the current version of the book, and “first editions” of that one might be going for less than £5. But that is the version that was edited and re-published in 1992, after the original had gone out of print. And it is not quite the same book.

In his introduction to the 1992 revised edition, Pratchett said The Carpet People “had two authors, and they were both the same person”. When the Discworld novels began to sell and demand for Pratchett’s debut novel went up, he told the publishers that he needed to do some re-writes, and the resulting new edition of the book was “not exactly the book I wrote then” and also “not exactly the book I’d write now”, but rather a joint effort between 17-year-old Pratchett and 43-year-old Pratchett.

Pratchett described the key difference as being that, back when he first wrote the book, he “thought fantasy was all battles and kings”. Two decades and several Discworld books later, however, he had changed his mind and decided that “the real concerns of fantasy ought to be about not having battles, and doing without kings”. As a result, as Andrew Butler puts it in his unofficial companion to Pratchett’s novels, the book transformed itself from an homage to Tolkien and The Lord of the Rings, to a parody of it.

The Carpet People Mark 1 – Suppressed Humour

It is no surprise that a fantasy novel written by a teenager in the late 1960s paid homage to The Lord of the Rings. Most of the fantasy novels written in the latter half of the twentieth century owe at least something to that trilogy and young writers will always be heavily influenced by their favourite authors (Tolkien being a favourite of Pratchett, who used to read The Lord of the Rings every year when he was a young man). The story features a long journey undertaken by a group of characters across a hostile landscape, including a a magician/shaman called Pismere who bears some resemblance to Gandalf, a mysterious wanderer with excellent fighting skills called Bane who is very much like Aragorn (especially in his Strider persona), and on their journey they have to fight the Orc-like Mouls.

Pratchett spent several years developing the story, which originally appeared in the form of short stories in his local newspaper the Bucks Free Press. While working on it, he often wrote to his friend Edward James, who was studying History at Oxford at the time, and who later wrote an account of the genesis of The Carpet People for a book he co-edited in which he quoted some of these letters. James suggests that Pratchett was “deliberately suppressing” the humour that would later make him famous in that first edition, creating a story that was “a relatively straight-forward telling of epic events in the lives of these people who live in the Carpet”.

The Carpet People Mark 2 – More Jokes, Fewer Kings

Some of the changes between the two versions of The Carpet People are relatively superficial, but they shift the book from Tolkien-esque fantasy to comedic parody. The 1971 description of the chieftain Glurk, for example, said he was “a man of few words, but words worth waiting for”. By 1992, this had become “a man of few words, and he doesn’t know what either of them mean” – which is both funnier, but also undercuts the character, giving the reader a much less favourable impression of him. James also notes that young Pratchett had got the idea from Tolkien that characters ought to speak in archaic English, but turned away from this idea later, so that in the 1971 edition characters say “Greeting” where in 1992 they say “Hello”, or “Begone!” instead of “Be off!”.

Some of the changes were a little bit more substantial, though the basic outline of the story stayed the same. James describes the changes to the 1992 version of the book as “Pratchettisation”, making the book fit Pratchett’s “cynicism towards politics, history, and traditional ideas of heroism, as well as towards battles and kings”. Our heroes Snibril, Pismere, Bane, and Glurk live in the Dumii Empire (loosely inspired by the Roman Empire) and their attitudes towards the Empire change quite a bit between the two versions. By 1992, Snibril’s love for the Empire has been cut back and Bane has become critical of the power of the Emperor. Pismere the magician in 1971 also becomes the more rational proto-scientist Pismere the shaman in 1992, talking about “correct observation followed by meticulous deduction” rather than using magical gibberish.

De-Tolkienifying the Story

The de-Tolkienification of the story can be seen most clearly in the changes to Bane’s character and the removal of his love interest Shenda in the 1992 version. In the 1971 original, Bane and Shenda are clear parallels to Aragorn and Arwen. Shenda and her father Noral are wights, a group of Carpet-dwellers who are similar to Tolkien’s Elves, as they built the cities of the Carpet long ago but have now declined in numbers, and they have a mystical aspect to them. Noral, who offers advice and attends a peace council in the original story, is clearly drawn from Elrond and Shenda from his daughter Arwen. Bane has connections to the wights just as Aragorn had longstanding connections with the Elves, and he and Shenda get married at the end just as Aragorn and Arwen do. In the 1992 version, however, Shenda has been cut out altogether and Noral’s role substantially reduced, with him making only one very brief appearance in chapter four. Bane, meanwhile, becomes openly critical of the Empire rather than being a fairly neutral exiled soldier, which moves him quite a bit further away from the Destined King Aragorn.

Some of the differences in tone – and Tolkien-lite writing – can be seen if you read the very first short story about Snibril, Bane, and Pismere, ‘Tales of the Carpet People’. This was published in the 2014 collection Dragons at Crumbling Castle, an edited collection of short stories aimed at children which gathered together a number of Pratchett’s early tales, and once again Sir Pterry could not resist editing the stories as he went, just a little bit. The editing is a lot less substantial, though, and you can see more of the original Tolkien homage left in the text. For example, there’s a reference to Pismere’s grandfather Robinson the Wanderer having walked across the whole Carpet, “right across and back again”, and at the end of the story Snibril leaves in the middle of a party because he has wandering fever, and when he is called on to make a speech, no one can find him. These hints clearly echo Bilbo Baggins’ behaviour; his adventure “There and Back Again” (the subtitle of The Hobbit) to the Lonely Mountain, and his disappearance in the middle of giving a speech at his own birthday party at the beginning of The Lord of the Rings.

We can also see the older editor-Pratchett adding the element of parody and gentle mocking in the 2014 version of this story. Pratchett’s introduction to the collection mentions that among the minor edits he made to the short stories included were things like “a little note at the bottom where needed”. Pratchett used humorous footnotes extensively in most of his works, but usually not so often in books for children, and not in a short story intended for a newspaper – so the footnotes in Dragons at Crumbling Castle are all most likely to be 2014 additions.

Weaving the Carpet

In ‘Tales of the Carpet People’, there is a very Tolkien-esque scene in which characters keep themselves going during a hard time by singing “the triumphant battle-song of the Fallen Matchstick”, complete with the lyrics to the battle-song, imitating so many sections of The Lord of the Rings in which characters sing songs of heroes or battles or epic deeds, and the whole song is written out in the book for the reader. Following the battle song, the narration observes that “they sang it in the old Carpet-language, which sounded a lot better” – another classic Tolkien trope, as many of the songs in The Lord of the Rings have, according to the narrative, been translated into the Common Tongue (i.e. English) from another language (such as Sindarin Elvish, or the language of the Rohirrim).

But then there is a footnote, which immediately undercuts the idea that the song sounded “a lot better” in its original language, saying, “But not much. Unless you are a tone-deaf snarg”. A scene which was, without the footnote, a moving scene showing people using song to encourage themselves and each other an a nice little homage to Tolkien becomes, with the addition of that footnote, a broadly comedic scene of a group of characters we are laughing at singing badly while trying to get something done, and a mockery of Tolkien’s tropes. With the addition of that footnote, what was once an homage to Tolkien has become a parody.

If you don’t have £400-£1000 to spare, reading ‘Tales of the Carpet People’ and its sequel ‘Another Tale of the Carpet People’ is probably the best way to get a sense of the tone of the original novel, even despite Editor-Pterry’s interventions. These were a lot less substantial when he was putting together the collection Dragons at Crumbling Castle than the 1992 re-write of The Carpet People had been – and you can always ignore the footnotes!

You can also read about the writing process on The Carpet People and the changes between the two versions in the chapter ‘Weaving the Carpet’ in Andrew M. Butler, Edward James, and Farah Mendlesohn’s book Terry Pratchett: Guilty of Literature, and you can see a lovely selection of charts and graphs examining the changes to various characters in the story put together by Brian Hainsworth at The Pratchett Project.

One of the very last things Terry Pratchett wrote was the Introduction to another compilation of his early stories for children, The Witch’s Vacuum Cleaner. “The young readers then weren’t like you in lots of ways” Pratchett told his young audience. “But they were exactly the same in that they wanted to read about other worlds, about strange creatures and characters, about extraordinary journeys and magic battles”. That is probably a pretty good summary of the changes between Pratchett the teenage writer in the 1960s, and Pratchett the adult writer in the 1990s. They were different in lots of ways, but exactly the same in the ways that mattered, writing about other worlds, strange characters, and extraordinary journeys – just like Tolkien before him, and just like many more writers to come.